Irish Universities Look to Graduates for Funds as Atlantic Goes West

Resource type: News

The Irish Times | [ View Original Source (opens in new window) ]

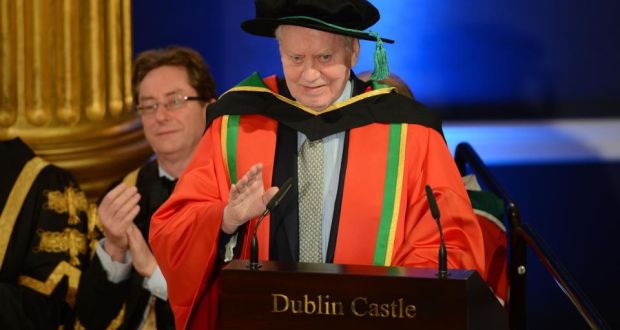

Philanthropist Charles F. “Chuck” Feeney being conferred an Honorary Degree jointly by the Universities of Ireland North and South at a ceremony in Dublin Castle. Photograph: Alan Betson / THE IRISH TIMES

By Louise Holden

Last year University of Limerick expressed its gratitude to the billionaire philanthropist Chuck Feeney, who helped to build the campus, the sports arena, the library, student and staff accommodation, professorships, scholarships and research laboratories. Atlantic Philanthropies, which has contributed €1.25 billion to projects in Ireland, many in higher education, announced it would wind down its Irish operations in 2016.

In an age of austerity it’s hard to see where the next fairy godparent is going to come from, so is this the end of large scale philanthropy in Irish higher education?

Maybe, but a new era of philanthropy is emerging, with the emphasis on “friend-raising” rather than fundraising. The inputs may be more modest, but the benefactors are great in number, according to David Cronin of the UL Foundation.

“This year we are celebrating the 25th anniversary of the foundation and, of the €200 million raised overall, a quarter has come in in the past five years,” says Cronin. “Philanthropy is not a historical thing, it still plays a significant role in universities achieving their ambitions.”

While Atlantic Philanthropies will be missed in Ireland, Cronin hopes this evolving sector will continue to be an important funding source, as long as universities are agile and creative in gathering it in.

“Apart from the money, one of the great gifts that Chuck Feeney gave to us was leadership,” he says. “He has been an exemplar and his influence will continue to reverberate for generations. Now it falls to us to realise what Bill Clinton has described as the ‘democratisation of giving’ – opening philanthropy up to everyone.”

The idea of crowdsourcing, raising funds for projects by gathering multiple small donations through social networks, is not unlike what Irish higher institutions now have in mind. All the universities are putting resources into building alumni networks and calling on graduates to invest in the alma mater. It’s a model that has long served US higher education, but it’s relatively new here.

‘Lifetime of giving’

Nick Sparrow, director of the Trinity Foundation, says the 400-year-old university is now building the notion of a “lifetime of support” among its graduates, starting the day they walk in the door.

“Like so many private universities in the US, we are trying to foster an understanding that from the day you start your undergraduate degree you are part of a class and will contribute throughout your life. Not every alumnus contributes in the US, but they do not consider it ridiculous to be asked to contribute. In Ireland we are finally at the stage where we can talk to alumni about our funding needs. There is an awareness that the Government can’t fund all projects. It’s exciting that it is at last a legitimate conversation to have with a graduate from Ireland. Ten years ago it wouldn’t have been possible.”

We’ve a long way to go before graduate giving reaches the value of the Glucksman or Feeney bequests. However, in the past 10 years, 10 per cent of all contactable Trinity graduates have made some sort of gift to the university. Although many are small, they have worth beyond face value, says Sparrow.

“Alumni giving is a key metric for how a university is rated. Many higher education rating systems will examine how many graduates are giving as an indicator of the institution’s standing. Also, it’s very important to large scale donors that they see others playing their part, even if it is on a smaller scale.”

Sparrow predicts alumni giving will grow, based on the current trajectory. “Ten years ago we were five decades behind the US when it came to alumni giving,” he says. “Now we are two decades behind, and one decade behind most leasing universities in the UK. It’s moving fast.”

New students at Irish universities may even be asked to start contributing while they study. “Student giving has become a reality,” says Sparrow. “We could be talking €10, but it’s the beginning of a lifelong engagement with the development of the university. The key is to excite donors with the projects they are giving to. We place a lot of emphasis on proper reporting, allowing people to see the benefits of their generosity in specific projects that would not otherwise have happened. Asking people to ‘give to distress’ may be seen as good money going after bad.”

Building new giving networks within the student and alumni community is a fine art. Maria Gallo, a researcher with St Angela’s College in Sligo, has written a number of papers on the topic and warns against applying marketing strategies that treat universities as commodities and students as customers.

“Students-turned-alumni have a vested interest in the reputation of their alma mater as it defines their intellectual journey and the value of their qualification. Moreover, the discourse of the student as a customer ascribes to a short-term student-institution relationship, terminated once the educational ‘product’ is accessed or consumed,” she wrote in a recent report on the sector. Universities must build a sense of pride – a brand to identify with – in order to foster the kind of affinity that underpins this kind of philanthropy. It goes some way to explaining TCD’s recent, somewhat controversial, decision to conduct a rebranding exercise in a period of cutbacks.

Meanwhile, in the University of Limerick, where the large scale largesse of donors such as Chuck Feeney and Lewis and Loretta Glucksman will soon be a thing of the past, they are quietly going about the business of harvesting generosity on multiple fronts. Last year the foundation pulled in €15 million in donations from a range of sources. In January it was announced that leading Irish-American philanthropist Loretta Brennan Glucksman was taking over the chair of the foundation, and that Chuck Feeney would remain on the board.

“We are not singularly dependent on one or two philanthropists,” says Cronin. “We have widespread relationships with leaders of business, arts, sport and culture. We pride ourselves on low overheads in the foundation and we are engaging successfully with a lot of leading figures in the Irish and Irish-American community. Our graduates are playing a key role. I’m always concerned when people think that philanthropy will be over when Chuck leaves.”

University of Limerick Foundation and Trinity Foundation are Atlantic grantees.