Welcome to the School of Resiliency

Resource type: Grantee Story

Featuring Oakland Unified School District |

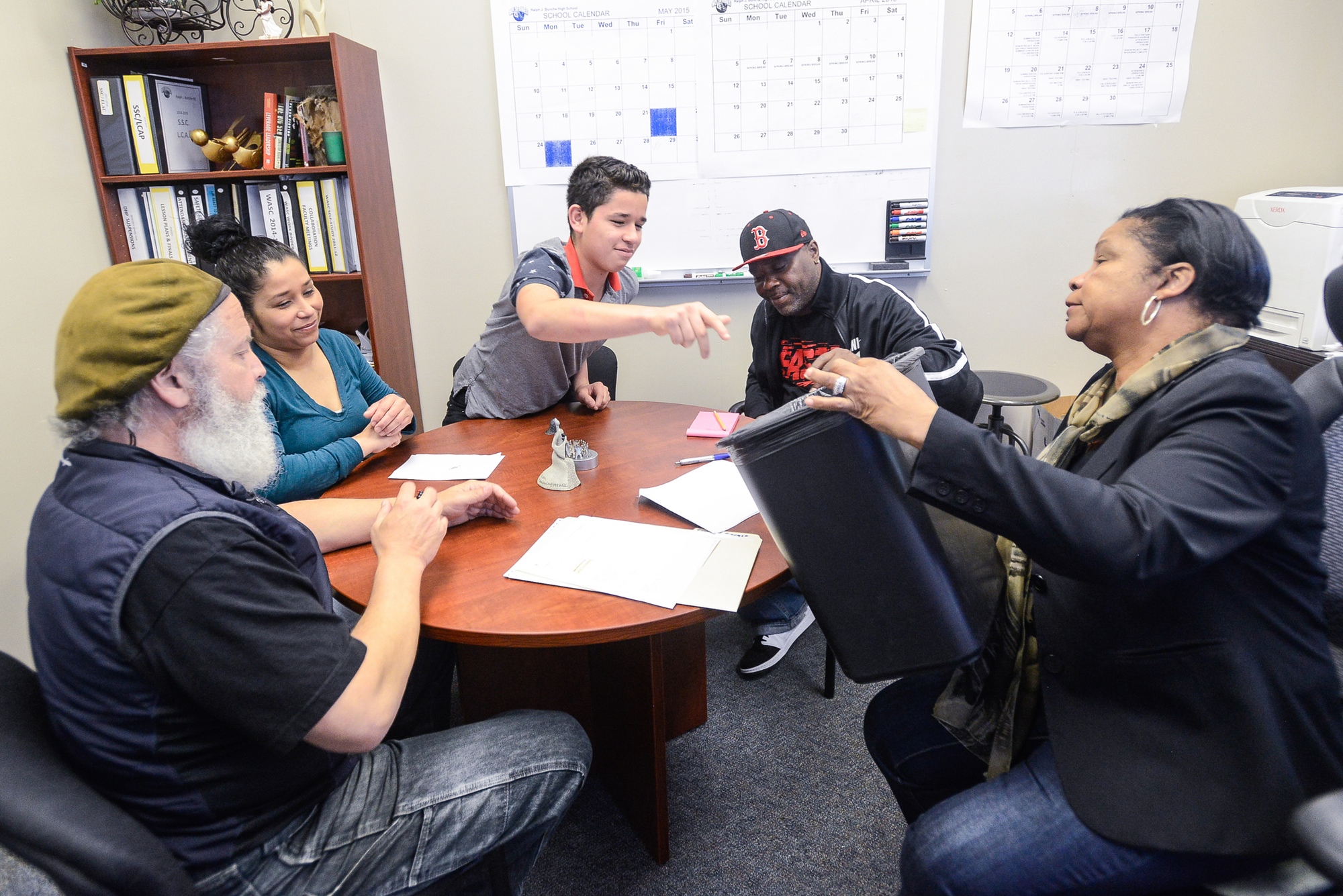

It’s a Thursday morning in mid- December and Betsye Steele, principal of Ralph J. Bunche High School, is holding her weekly new-student orientation session. She sits at the small table in her office talking with Antwon, the school’s newest student, and his grandfather. As they review Antwon’s academic record, Steele asks questions, jotting down notes as the 17-year-old shares about the courses he likes and those he found challenging. When it comes time to talk about Antwon’s disciplinary history at his previous schools, Steele looks through the sheets of paper detailing the young man’s transgressions and then stops, hands Antwon the stack of papers, and invites him to throw the sheets in a nearby garbage can.

“What happened before has no impact on what will happen here,” says Steele. “That’s all behind you. From today forward, we’re 100 percent focused on getting you to graduation.”

Like other continuation high schools in Oakland and elsewhere, Ralph Bunche is often viewed as the “last chance” school for its students, the vast majority of whom arrive in Steele’s office after unsuccessful experiences in one or more other high school settings. Many of the school’s 175 students have a history of suspensions and expulsions. Some have “rap sheets,” having been in and out of juvenile hall. Although barely past childhood themselves, some students have children of their own or are responsible for parenting their younger siblings. Some may live in a group home or on their own.

And while all of these realities can make just getting to school on time every day an accomplishment, Steele and her staff have set their sights on a bigger prize than regular attendance alone. They are committed to supporting students from that first intake meeting until they walk across the stage at graduation. Together, school staff and their partners have created an environment that marries discipline with respect, accountability with support, and an appreciation for the challenges facing students with an unflinching belief in their ability to graduate high school and take charge of their futures.

“We construct a plan for success for each student and then support them with the resources they need to make it to the finish,” says Steele. “Our students are bright young men and women with big dreams,” she adds. “Our staff creates a supportive, caring community to help students make meaning out of their education and realize those dreams.

A Culture of Discipline, Not Punishment

First time visitors to Ralph Bunche High School quickly sense something different about the “feel” of the West Oakland campus, even if they can’t quite put a name to what they see and sense among the students and staff. But ask anyone – from a teacher to a student to the office personnel – and they’ll quickly tell you what makes the school different: it’s the commitment to Restorative Justice as “a way of being together,” providing the framework for building and sustaining trusting relationships in and out of the classroom.

“Restorative Justice teaches a simpler, more humane way of being that is focused on communication and being in relationship with each other,” explains Eric Butler, the Restorative Justice coordinator. Rather than continuing the pattern of suspensions and expulsions that are all-too-familiar to their students, the staff at Ralph Bunche focuses on developing clear agreements and building a culture of trust and accountability, so that when conflicts arise, there’s a strong foundation and common framework for resolution. All staff members receive training in restorative practices, and Butler provides one-on-one support to teachers as they put the concepts into practice in their classrooms.

“It’s the difference between discipline and punishment,” says Butler. “If I focus all of my energy on punishment, I’m doing that for myself, not for the student whose behavior I am trying to change. In a culture of discipline, we’re treating incidents as learning opportunities – as a chance for students to grow.”

The approach is working. The school doesn’t suspend or expel students, and has a track record of resolving conflicts with conversations rather than confrontation. More than 90 percent of the students who arrive at Bunche as seniors walk the stage at graduation – a testament to both the abilities of the students and the culture of success that has been nurtured by Steele and her team.

The commitment to Restorative Justice means that students leave with more than a diploma, says Vice Principal Donnell Mayberry. “It gives students back the responsibility of self-managing and teaches them to be good communicators and good listeners,” he adds. “Those are skills they need for life.”

Intentional Conversations

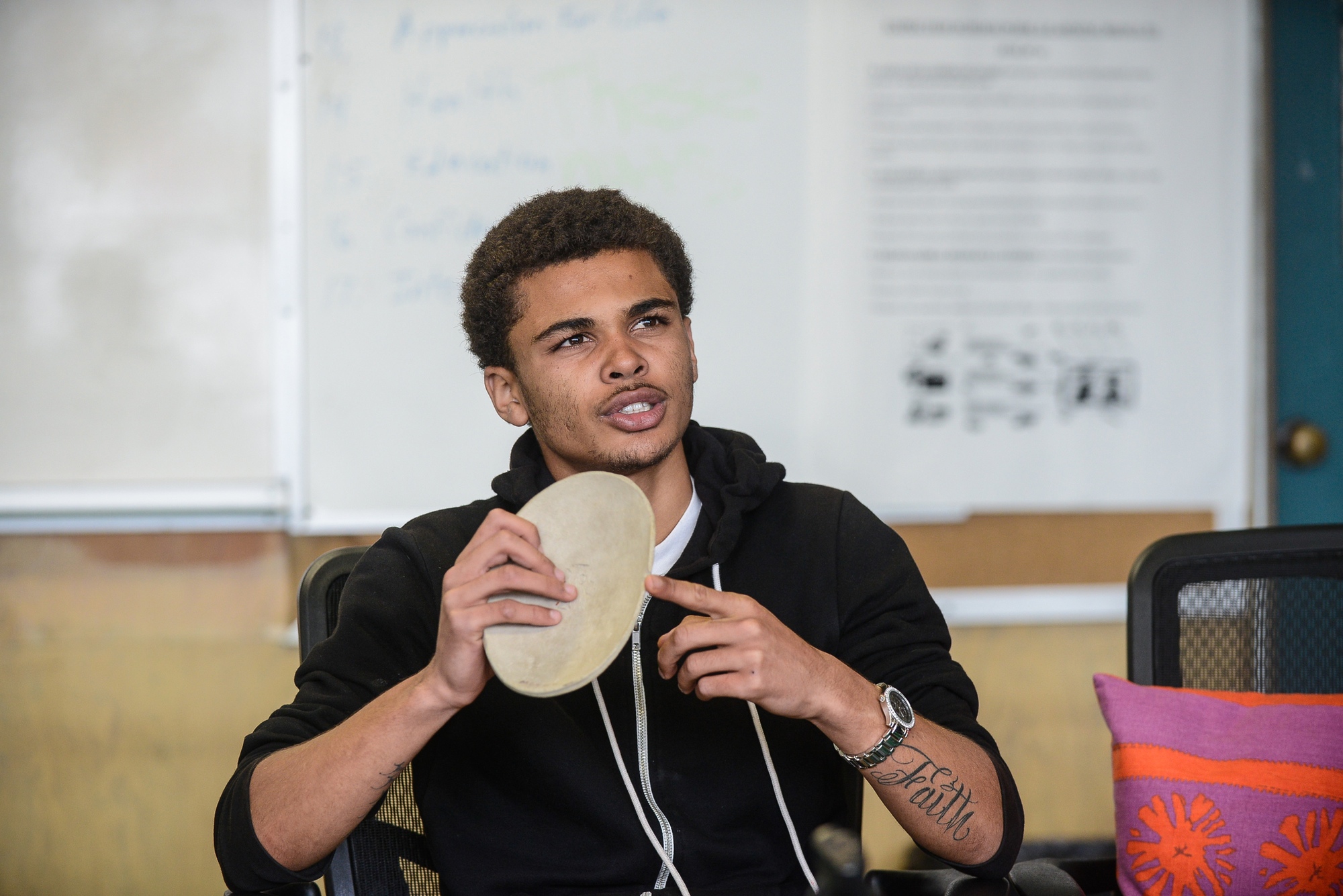

Butler’s classroom is home to the school’s primary space for holding Restorative Justice circles, a foundational element of the practice. Circles are used to facilitate intentional conversations and to build a culture of understanding and trust. Butler or another staff member may use a circle to talk through a dispute between two students or a conflict between a student and teacher. Circles are also used to engage a broad cross-section of the school community in important conversations, and to create a space for many voices to be heard and valued. The school staff holds circles at the start of the year and circles are routinely used to welcome new students. Instead of the typical job interview for potential teaching candidates, finalists for an open position join staff and students in a circle.

One Tuesday afternoon, Butler has invited members of the men’s basketball team to his classroom for a circle. After losing an important game the prior Friday, members of the team had responded with anger and frustration at one another, the referees, and their opponents. It was a disappointing moment for the team, and for the adults at the school, who knew the young men were capable of better – on and off the court.

Seated around the circle, the players begin by reliving the game, their frustration rising as they reflect on missed plays and bad calls by the referees. Over time, though, with the skillful facilitation of Butler, their mood shifts and they become more reflective. “We didn’t play as a team,” says one. “We got upset and lost focus,” says another.

By the end of their time together, the players have complimented one another on their strengths and reflected on their challenges, and their coach has done the same. “The problem is you don’t trust one another,” says Coach Leon. “You have to be able to fully trust one another if you’re going to play and win as a team.”

The experience with the basketball team is a powerful example of the skills students are gaining through the school’s commitment to restorative practices, says Steele.“The coach could have yelled at them and punished them for their behavior, but instead they were able to stop and reflect. They were able to cleanse their angry feelings at each other, at the referee, and at their coach,” she observes. “Most students don’t have that kind of opportunity for growth and closure.”

Teaching and Learning: Making Meaning Together

Recognizing that many students arrive on campus with few positive academic experiences and little confidence in their academic abilities, teachers are intentional about connecting classroom learning to students’ lives and creating spaces for student voice to be heard and reflected in the design and structure of classes and assignments.

In the wake of the highly publicized killings of unarmed African American men by White police officers in Ferguson, Missouri, and Staten Island, New York, English teacher Sean Gleason developed a six-week unit that combined the study of protest literature with an opportunity for students to express their own anger and frustration at current events. After a close reading of James Baldwin’s, “A Letter to My Nephew,” for example, students were tasked with writing their own letters to reflect on current injustices, much as Baldwin did in 1962. Later, during a schoolwide assembly, one of Gleason’s students reads a poem she wrote as part of another assignment in the same class.

In Nestor Gonzalez’s third-period art class, students begin their time together with what the veteran teacher describes as a “brain dance of mindfulness.” Standing in a circle, they toss a medicine ball back and forth as they talk about their day and gently transition to their class time together. Later, Mr. G (as he is known by students and staff alike) walks around the large worktable where students are in various stages of completion of sketches in their art journals, offering technical tips on shading or scale, and inviting students to talk about their work with their classmates. The environment is relaxed, and students are engrossed in the task at hand.

“We have to create an environment where it is safe for students to learn, and to have fun as they are learning,” says Gonzalez. “It can take two to three months to get to a place where a student trust me,” he adds, noting that many students have put up protective “shields” in response to a history of negative school experiences.

Besides encouraging self-expression through art, Gonzalez has dedicated a giant white board to student expression – from graffiti to poetry to whatever thoughts are on their hearts and minds on any given day. The space provides Gonzalez with insight into students’ thoughts, moods, and needs. Student contributions to the white board have been the impetus for formal art projects and a few words written after a particularly rough night or morning can signal that a student is struggling and needs additional help and support.

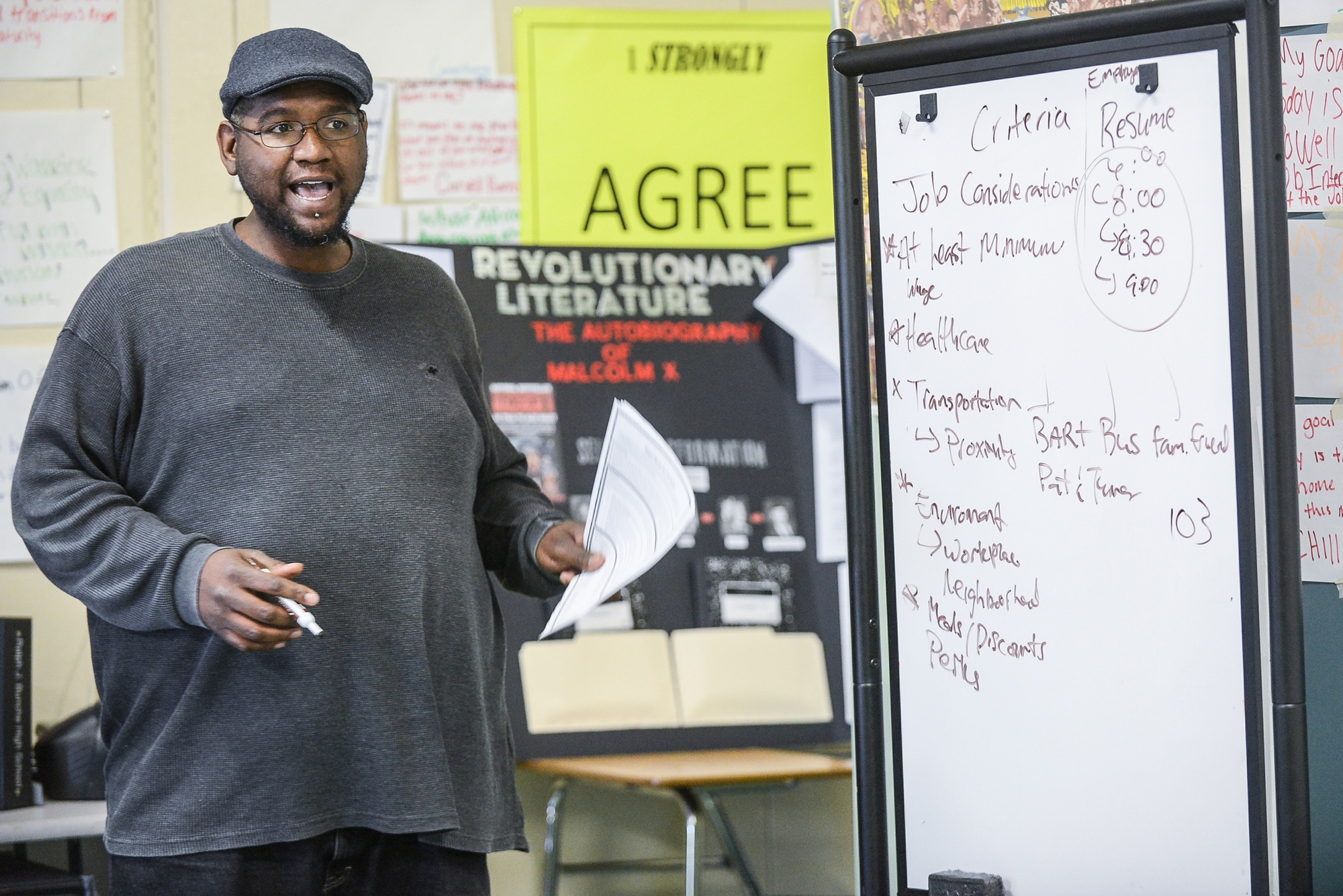

In addition to the traditional academic subjects, Ralph Bunche offers a course for African American males as part of the school district’s African American Male Achievement program. The Manhood Development class combines literature with class discussion to create a unique space for students to grow in their appreciation for the gifts and contributions of African American men, and to develop the confidence and self-esteem critical to their personal success.

“I can’t expect them to retain everything we talk about, but what I can hopefully give them is pride of who they are and where they come from,” says Aquil Rasheed, who teaches the course. Through their readings and discussions about African American history and writings, students grow in their appreciation for the struggles and contributions of those who have gone before them, he adds.

Preparing for Graduation

Students arrive at Ralph Bunche at different times of the year and at different stages of their high school career (though most arrive in their junior or senior year). All are focused on one singular goal: graduation. In addition to supporting students’ efforts to earn the 190 credits they need to receive their diploma, school leadership is advancing three initiatives designed to help students develop important academic and life skills that will be critical to their success after graduation.

“Our goal is that our students graduate with a vision for their life after high school,” says Mayberry. A Linked Learning program, begun in Fall Semester 2012, connects classroom learning with industry-specific knowledge and job skills. The first area of focus for the Linked Learning initiative is the hospitality and tourism industry. Through guest lectures, internships, site visits, reading, and discussion, students are learning about the growing industry and exploring both academic and career options after high school. Linked Learning instructor Esther Dixon has forged a partnership with Visit Oakland, a local non-profit focused on increasing tourism in the city, and Visit Oakland CEO Allison Best has provided the class with resources and assisted in outreach and partnerships with areas businesses in the hospitality and tourism industry.

All students are required to complete a senior project as a condition of graduation. Students choose the topic and then are coached and supported by one of the teachers on the staff team that leads this effort. The project is an opportunity for students to demonstrate core academic skills, explore a critical issue in the Oakland community, and begin to develop a plan for life after high school. One student, for example, used his senior project as an opportunity to explore a career in fire fighting. He researched the career online, conducted interviews with fire fighters at a nearby fire station, and created a road map for his future. Because of the research and the relationships he developed, the student is now enrolled in a fire fighter training program.

Another critical component of preparing students for graduation and for life is developing students’ reading ability. Many students arrive at Ralph Bunche with reading levels well below the average for high school students. Through improved diagnostics, one-on-one tutoring, and online tools that can be tailored to student needs, the goal is to accelerate progress. Two staff members — Romany Corella, a teacher on special assignment, and Alice Swafford — work with students and support other teachers to provide personalized support for struggling readers across subject areas. Besides the focused work to improve students’ reading levels, Corella is focused on instilling a love for reading among students, and a culture of reading for pleasure among both students and staff at Ralph Bunche. The school has adopted a 22-minute silent reading period one day a week, and students are encouraged to explore both fiction and non-fiction and discuss what they’re reading and learning with their classmates.

Promises Kept

The educational supports and the collective commitment to a restorative school culture are critical elements of a promise that Steele and her staff make to their students when they enroll at Ralph Bunche: follow the plan and you will graduate and earn a high school diploma.

Although students may initially be skeptical of this assurance, on Graduation Day all traces of doubt have been replaced with confidence and hope for the future. As Pomp and Circumstance plays, students enter the auditorium in pairs, and many dance down the main aisle towards the stage, as family and friends clap and shout their approval and congratulations. It’s a scene of pure joy and celebration.

In their short time at Ralph Bunche (on average, students are there for about one year), the graduates have created a new future for themselves. With the assistance of a staff committed to their success, students have defied the odds and silenced the skeptics. Although they’ll walk across the stage with many of the life challenges they carried with them when they arrived at the school, they’ve grown more resilient, more willing to trust, and more able to dream.

In the last few minutes before the graduates are handed their diplomas, classmate and valedictorian Terrance Tucker shares some final words of encouragement, echoing the support that has enabled him and his classmates to make it to that special day.“We are the holders of the dream. We are creators of our own future. We have the strength to overcome any obstacle.”

Circles of Truth and Healing

Eric Butler holds the talking piece in his hand and asks a question of the students and staff gathered in Room 7 for a Restorative Justice circle: “Was there a time when you were treated unfairly by police?”

The room is quiet for a moment with the weight of the question. Only a few days earlier, a grand jury in Ferguson, Missouri, had voted not to indict the White police officer who had shot and killed Michael Brown, an unarmed African American 18-year-old. The decision had sparked protests throughout the country calling for justice and an end to the criminalization of Black boys and men.

“It’s important to create a space to bring in what is real in the lives of students,” says Aquil Rasheed, who teaches the Manhood Development course at Ralph Bunche and joined with other African American men on staff to convene the circle.

Over the course of the next hour, students and staff share their experiences with law enforcement and their feelings of anger, frustration, and sadness at the recent verdict. Towards the end of their time together, they each are encouraged to imagine how things could be different, better.

For Butler, the opportunity to express feelings of anger and frustration and to share hopes and dreams is therapeutic for adults and students alike. “We are healing each other in a way that is unbelievable,” he says. “You can actually see the transformation right there in the circle.”

Forging New Relationships between Staff and Students

By the time most students arrive at Ralph Bunche High School, they’ve become disillusioned with school and distrustful of teachers and school staff.

“They’ve put up walls for their own self protection,” says Kameelah Mitchell, who coordinates the student leadership program. It takes a community of committed adults to break down those walls and help students begin to build trusting relationships with adults, she adds.

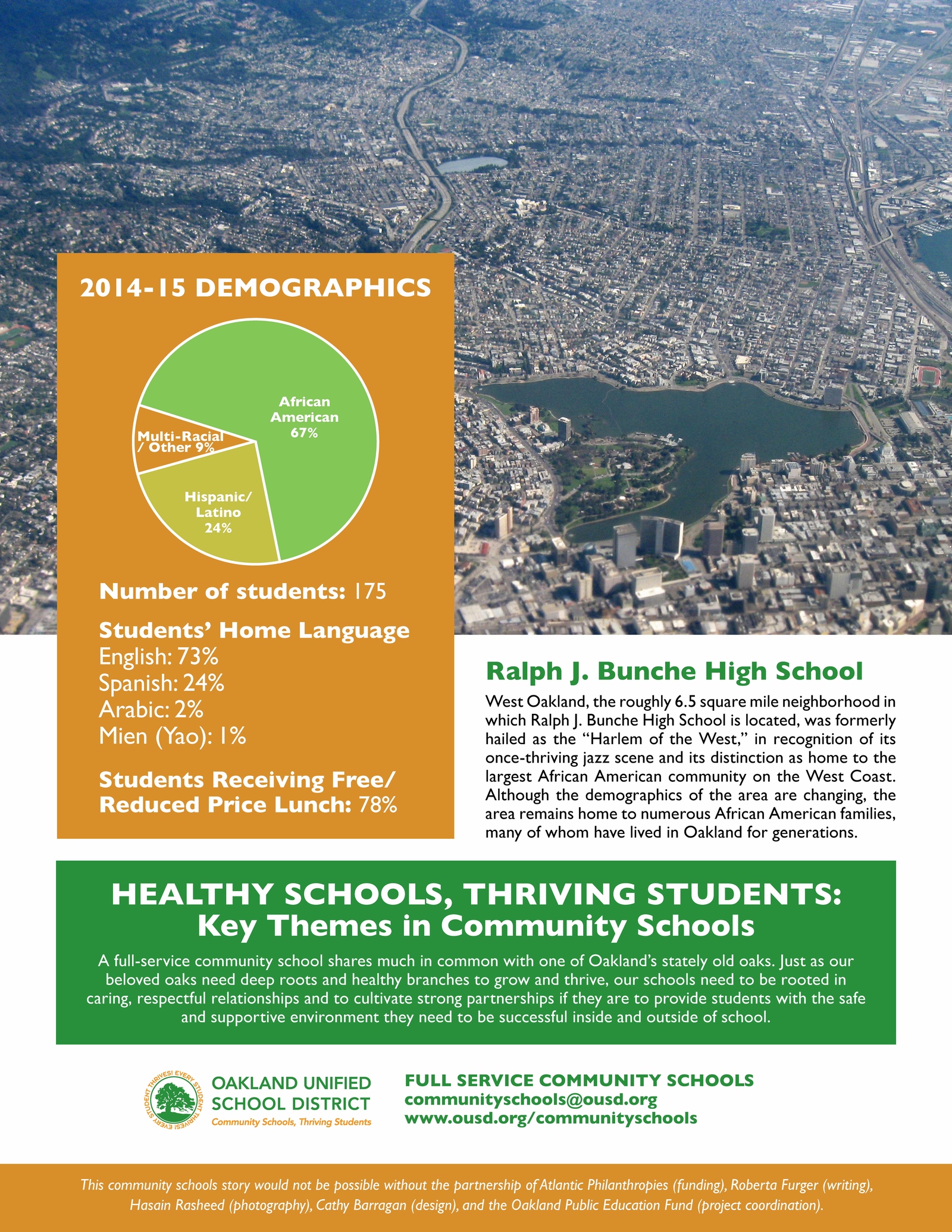

Principal Betsye Steele has taken care to assemble a diverse team, and places a high priority on having staff that reflect the community and cultures of the students. (The student body is 67 percent African American and 24 percent Latino.) Both she and Vice Principal Donnell Mayberry are African American, as is the school counselor. The diverse teaching and other professional staff include Latinos and African Americans.

“I came here because I wanted to be a role model for young black men and to help them get back on track,” says Mayberry. “I’ve never been in another school like this in my life. There is so much caring, so much support, so much love.”

When tragedy strikes, that love and support becomes especially important and can make the difference between a student staying in school or dropping out. That was the case in late December 2014, when staff received word that a student had been shot several times at close range. The young man was seriously injured and for the first few days it wasn’t clear whether he would survive.

Restorative Justice Coordinator Eric Butler was at the hospital nearly every day, providing support and encouragement to the student and connecting his family to much-needed services. Other school staff also visited the hospital. “At that point in his life, it was important that he knew we were there for him,” says Butler, “and that we would welcome him back when he was able to return to school.”