Amplifying Change: The Making of a Digital Archive

Resource type: News

Digital Repository of Ireland | [ View Original Source (opens in new window) ]

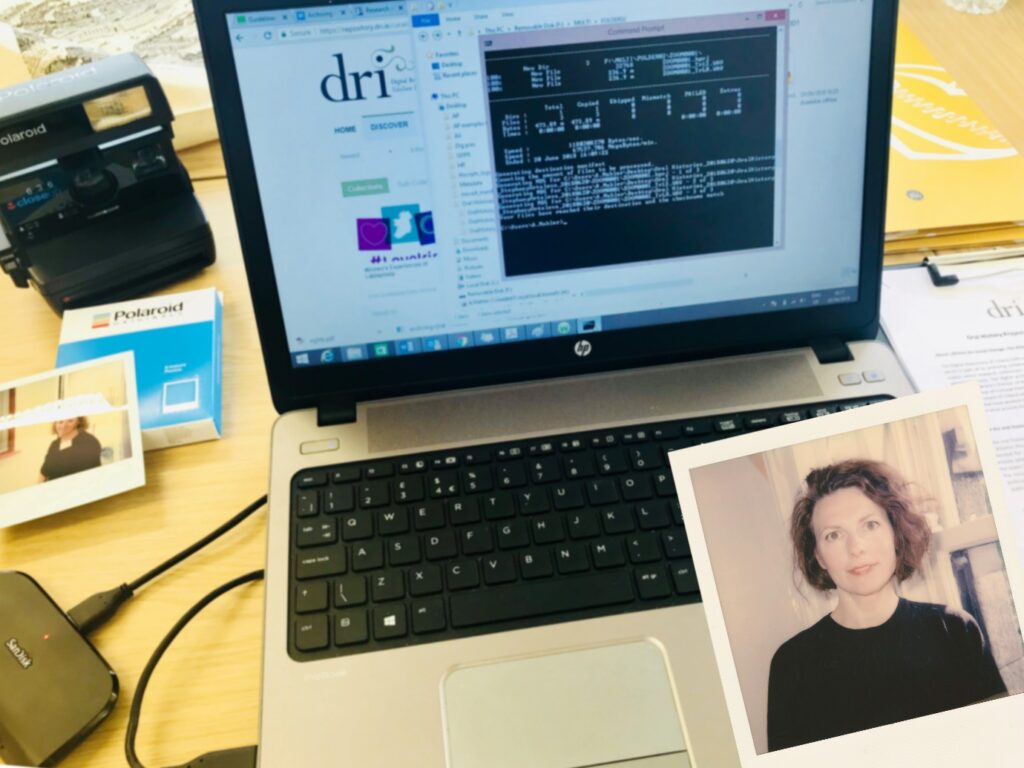

Anja Mahler, Digital Archivist, Atlantic Philanthropies Archive Project, Digital Repository of Ireland, wrote this article about what goes into making a digital archive in 2020. We’ve curated it for Atlantic’s site to illuminate the behind-the-scenes thinking to make an enduring digital archive.

Foreword

Before I took up the position of digital archivist for the Atlantic Philanthropies archive project in early 2018, I did not know much about Chuck Feeney and the extent of his philanthropic investment on the island of Ireland. Conor O’Clery’s book The Billionaire Who Wasn’t: How Chuck Feeney Secretly Made and Gave Away a Fortune provided me with great insight into the work of the Atlantic Philanthropies. Soon after I took up my position, I travelled to New York to visit Cornell University. I got to see the physical archive held at the Division for Rare and Manuscripts Collections and I also gained exclusive access to The Atlantic Philanthropies grant management system for Ireland and Northern Ireland. It was then that I grasped the great extent of this archive. It was not, however, until I got to look closely at the grant files, which contain records that document the entire life cycle of grants-from proposals to final reports and rich ephemera, that I experienced a sense of awe because I realised the vast impact of the Atlantic Philanthropies. I recall cataloguing the document Action Plan on Bullying and how that acted as a catalyst for me to realise the sheer amount of combined energy needed to bring about societal change. My dear colleague Phoebe Lynn Kowalewski, the Atlantic Philanthropies Archivist at Cornell University Library, put it this way to me very recently:

The value of these archives is that while anyone can see from a quick google search what Atlantic did in Ireland, these resources provide a more intimate view of the societal issues that Atlantic thought to improve and thought processes that made these improvements happen.

Introduction

In addition to highlighting what this archive seeks to reveal – the processes, methods and mechanisms behind social, economic and historical change on the island of Ireland – I wanted to give insight to the thought processes, methods and tools used to build this research resource. In writing this blog, I am wearing my digital archivist hat, but I do hope this look behind the scenes is of interest beyond the archival community.

Computational thinking

Contents (business records, reports, and ephemera) and contexts (original arrangements of records and memories from individuals) are required to change from the realm of corporate memory to collective memory. To enable this lifecycle change of data for this archive, we drew on computer science strategies such as finding the logical structure of a task, modelling data in a more accessible form, and figuring out how to apply iteration and algorithms to break tasks into pieces so that they could be automated.

Creating a collection development strategy

My objective for this project was to create an online archive and a virtual exhibition platform and the complexities inherent to that task boil down to two problems: taxonomies and extent. In other words – what are the resources? how are they retrieved? and how many resources can we process in the time we have? I worked closely with the project historian to figure out how to best develop this collection. We identified a pattern of Atlantics impact on the island of Ireland, categorised that information and modelled it into a collection development strategy by assigning the appropriate number Atlantic’s grantees, grants and grant documentation, and associated oral histories and essays for each theme.

The model enabled us to arrange contents on DRI, where we preserve the original cooperative arrangement of records sorting by grantee and grant number, and for the virtual exhibition platform where we allow for curated exhibitions by themes and sub-themes.

For this project, curatorial selection and archiving of records existed in tandem. For the archivist, the model enabled the indexing of contents that would facilitate content retrieval on both the repository and the dedicated web platform. For the historian, the model provided a framework which ensured that the story of Atlantic’s impact is told broadly by identifying grants and oral history interviewees that would spread evenly over themes, while considering geographical parameters.

The collection development strategy provided us with a close approximation of how many items we could include, basing our processing time on previous experiences.

Mapping out workflows with PREMIS

A more accurate estimation of extent was achieved by mapping out the processes involved for each record’s journey from corporate archive to public archive, distinguishing between born-digital and digitised content. To map the workflow, I used Preservation Metadata Implementation Strategies (PREMIS). PREMIS was originally designed to guide the documentation of preservation action in a repository. For this archive project, it served as a tool to guide the design of digital preservation workflows prior to ingest (accessioning). Employing abstraction for a task breakdown that categorises ‘object’, ‘agent’, ‘event’, and ‘location’ aided the visualisation of each record’s journey. This technique helped to identify scope in more detail and allowed for the development of an effective communication strategy amongst partners by identifying agents responsible for each task.

Electronic transfer with BagIt

Each record would travel quite a bit going through many hands and systems before becoming ingested to DRI. Key to digital preservation is fixity information, otherwise known as checksum creation and verification. This enables electronic transfer by ensuring the file is transferred with maintained integrity. For electronic transfer with fixity between Cornell University and DRI, we chose BagIt. The BagIt specification is a hierarchical file packaging format for the creation of standardised digital containers called ‘bags’, which are ideal for transferring digital content. Derived from work by the Library of Congress and the California Digital Library, a bag is designed to create a common language for users exchanging digital materials, negating the need for expertise about others’ protocols.

In addition to fixity, BagIt will aid the exchange of information. In this case, we utilised BagIt’s tag option to exchange the persistent actionable identifier (DOI), which is minted at the point of ingest to DRI, with Cornell University. We will use the BagIt command ‘–external identifier’ when writing a programme that exports the entire data set into the final bag including a label or tag containing the DOI (digital object identifier).

Digital preservation actions on the command line

For digital preservation actions such as maintaining file integrity, I use the command line. The command line is an interface for typing commands directly to a computer’s operating system. One command I use often is called copyit.py, authored by Kieran O’Leary. The programme copies a digital object with fixity information from one location to another and supplies a manifest. I would, for example, copy the oral histories from their SD cards by using this method, ensuring file integrity is maintained at every step in the journey before ingesting to DRI.

Ingesting records with Open Refine

Another step to ensure best practice in digital preservation is quality assurance and this is as vital for records as it is for their catalogue or in other words the data and its metadata. For this archive, I created metadata by using DRI batch metadata template, a spreadsheet that allows users to input bulk metadata. (I have described the benefits for this archive here.) In this way, I could use OpenRefine, a powerful tool that allows for cleaning metadata and transforming it from one format into another. After quality assurance, I use the export via template function to export all the fields I have created into XML format. This format is both human-readable and machine-readable and aids the batch ingest process developed by DRI. You can find more details about this process here.

Describing records with Dublin Core Qualified

The aim of metadata to enable resource discovery is achieved by using standards. It allows for metadata to become linked and shared widely. For this archive, we used Qualified Dublin Core metadata standard, guided by Qualified Dublin Core and the Digital Repository of Ireland. One of the criteria for choosing this standard was to be able to create relationships between the different collections of oral histories and the grant documentation using the facet <dcterms:relation>. To populate information for each facet within this metadata standard, for example <dc:subject> or <dc:coverage>, controlled vocabularies and guidelines were used. Controlled vocabularies are standardised and organised arrangements of words and phrases that provide a consistent way to describe data. The Library of Congress Subject Headings is a great example. This consistency was key to arranging data in two different ways so that the discovery of resources is made possible on DRI and the designated web platform made with an application called Spotlight. Metadata is preserved in form of XML in the repository and from here it becomes displayed on different interfaces through mapping and automation. Because the metadata is standardised in a way that is transparent to others it is enabled to exist outside of DRI, reaching even greater audiences.

Retaining access permission

On a final note, I would like to mention the endeavour to increase the durability of contents presented in this archive. To become suitable for public consumption online, each record was appraised for sensitive information and redacted where necessary. This process happened in close collaboration with content creators from multiple sectors such as academic institutions and non-governmental organisations. With incredible effort, access permission agreements were obtained, and copyright issues resolved in careful consideration of legal jurisdictions of Irish, British, European, and American law.