Keeping Memory Alive

Resource type: News

Gara LaMarche |

It wasn’t easy ten years ago when 19 people from diverse backgrounds in Northern Ireland came together to talk about setting up the Healing Through Remembering (HTR) Project. Intense feelings and bitter memories of the conflict made it sometimes hard to be in the same room with one another.

It wasn’t easy ten years ago when 19 people from diverse backgrounds in Northern Ireland came together to talk about setting up the Healing Through Remembering (HTR) Project. Intense feelings and bitter memories of the conflict made it sometimes hard to be in the same room with one another.

After months of meetings, this group of ex-prisoners, police and army officers, survivors of the violence, community workers, academics and clergy agreed to call themselves the board of HTR. They worked together for two years, writing the Atlantic-sponsored Healing Through Remembering Report, which remains one of the most significant documents on how to deal with the past, including the painful memories of Northern Ireland’s conflict. They developed plans for a second phase, a not-for-profit voluntary organisation that facilitates a society-wide debate on how to deal with the past in an effort to build a better future.

Throughout Atlantic’s history, the preservation of memory and archive, as HTR has done, has been an important aspect of our work in two different veins. Through our Reconciliation & Human Rights Programme, we have supported efforts to help reveal and heal the past and shape the future in Northern Ireland and South Africa. In addition, as a foundation spending down its assets, we are engaging scholars to chronicle the legacy of our founder’s generosity, and the lessons from our body of grantmaking that may help others in the field and prospective philanthropists benefit from what has and hasn’t worked at Atlantic.

A growing body of literature suggests that the recollection of painful events, together with dialogue about the past, is among the peace-building initiatives that help achieve long-lasting reconciliation. As an example, most of the original 19 Healing Through Remembering Project board members, diverse as they are, remain very active today in the organisation they created.

Current technology helps preserve, document and disseminate the stories of oppressed people as a means of coming to terms with human rights abuses and helping others appreciate the struggle to democracy. The artifacts and information are often fragile and easily lost or sometimes intentionally destroyed, so there is urgency to recover and preserve suppressed knowledge, particularly when it challenges the dominant narratives of history.

|

| An archival scan from the Traces of Truth digital archive, Kitskonstabels in Crisis, Institute of Criminology, University of Cape Town, 1990. |

In South Africa, a strong component of our Reconciliation & Human Rights Programme has been to preserve the archive on colonialism and apartheid as well as of the anti-apartheid struggle. Atlantic has supported a dozen or more projects, including the establishment of Traces of Truth, a non-commercial digital archive of the materials from the Truth and Reconciliation Commission to preserve the findings of the largest survey of human rights violations in history.

Several initiatives broke new ground in the field of heritage and reconciliation, and some of our grantees have taken strong activist roles. We helped establish and grow both the South African History Archive (SAHA) and the Gay and Lesbian Archives (GALA) of South Africa, and both collections are housed in the Department of Historical Papers, another grantee, in the William Cullen Library at the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg. GALA has emerged as a cutting-edge archive combining the collection of documents, oral histories and artifacts. It has a number of outreach programmes, and a publishing and film-development profile to disseminate and popularise the findings of its research and the contents of its collections. In an effort to help deepen civil society’s capacity to understand the struggle for its independence, Atlantic supported a bold effort by SAHA to bring to light the 1982 Steyn Report, which revealed the role of apartheid police, intelligence and senior military generals in a clandestine project, called “Öperation Pastoor,” to destabilise the transition to democracy.

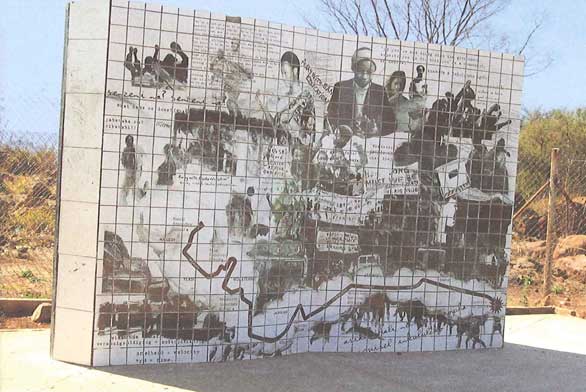

Disseminating the archival information broadly is a key goal of our grantees. In 2006, we sponsored SAHA’s collaboration with the Sunday Times Heritage Project to remind people of the anti-apartheid struggles. The broadsheet newspaper constructed 40 public memorials of unheralded individuals and events around the country, and the most innovative aspect of the project was supporting scholars and young people to research and build their own memorials to commemorate historic events in their towns.

The South African History Archive’s research, sponsored by Atlantic, led to 40 memorials commissioned by The Sunday Times for its centenary. This wall dedicated to Youth Leader Tsietsi Mashinini resembles a giant exercise book and features a montage tracing the route of the 1976 march that started the Soweto uprising. This memorial stands opposite Morris Isaacson High School in White City, Jabavu, where the protest against the use of Afrikaans in schools began.

Atlantic’s largest grant in its memory portfolio restored and turned the Johannesburg Fort at Constitution Hill into a museum on the struggle against apartheid. Built in the late 19th century, the Fort–Johannesburg’s equivalent of Robben Island served as a prison where many political activists, including Mahatma Ghandi, Nelson Mandela and Tsietsi Mashinini, the leader of the 1976 Soweto uprising–were detained. To symbolise the victory of ordinary people over apartheid, South Africa’s new Constitutional Court stands adjacent to the Fort. We also supported The Nelson Mandela Gateway at Robben island and The District Six Museum, which is dedicated to preserving the history and memory of the forced removals of 60,000 residents from this racially-mixed section of Cape Town under apartheid. In addition, we helped fund the On-Line History of the Liberation Struggle and several documentaries as part of an effort to promote democracy.

The isolation cells at the Johannesburg Fort at Constitution Hill in South Africa were used to hold political prisoners while awaiting trial.

In Northern Ireland, Atlantic also supported the University of Ulster and Queen’s University Belfast to establish the Northern Ireland Social and Political Archive: Access Research Knowledge (ARK) to collect information on the social and political life of Northern Ireland, referring both to the Troubles and to more normal aspects of life. The archive and Web site, like Traces of Truth in South Africa, makes widely available research about reconciliation in areas of conflict in order to promote healthy and vibrant democracies and inform practices during the transition from conflict to peace. In another effort, a grant from Atlantic supported Reminiscence Network Northern Ireland to coordinate a three-year project, called “Valuing Heritage by Valuing Memories,” in partnership with four museums. The emphasis was engaging local people, particularly older citizens, and organisations in grassroots reminiscence work that resulted in 12 case studies. For example, ten members of the Craigavon and Banbridge Carers’ Men’s Support Group received respite from their challenging carer roles by bonding over reminisces of their military service, which became a well-received booklet; and several have continued creative writing and sharing stories with their families, in some cases for the first time.

At Atlantic, we are also documenting our own story as we move closer to spending down our endowment and closing our doors by 2020. Tony Proscio, a noted philanthropic analyst—in collaboration with Joel Fleishman, Professor of Law and Public Policy and Faculty Advisor of the Center of Strategic Philanthropy and Civil Society in the Sanford School at Duke University, and former President of the U.S. operation of Atlantic from 1993 to 2003—has produced Winding Down The Atlantic Philanthropies—The First Eight Years: 2001-2009, the first of a three-part report on the foundation.

In 2005, Atlantic also engaged the Oral History Project at Columbia University to document the initiatives of our Founding Chairman Chuck Feeney and the foundation, and it has recorded 140 interviews of his longtime colleagues and business associates as well as staff from the early years of the foundation. At Limerick University in Ireland, Mr. Feeney has participated in an oral history project that tells the story of his motivation and passions for his business and philanthropic ventures.

Finally, Atlantic also supports the largest oral history project in history, StoryCorps, subject of my December 2009 column. This innovative venture — full disclosure: after learning more about StoryCorps through Atlantic’s grant, I agreed to join its Board — preserves the memory of everyday people across the United States, including individual struggles and triumphs related to age, race, gender and immigration. To date, StoryCorps has recorded and archived over 30,000 stories, involving more than 60,000 participants.

George Santayana famously said, “Those who cannot remember the past are condemned to repeat it,” but in fact archive and memory are critical not only to inoculate against the repeat of tragic history, like civil conflict or apartheid. Connection with the past can also preserve and extend the lessons of those who resisted, worked for peace, or came together to forge a better world. That’s why Atlantic believes so strongly that efforts to remember and preserve the memory of conflict and resolution—with all its successes and failures—are a critical component to bringing about lasting change for vulnerable and disadvantaged people.