Limerick’s quiet revolution

Resource type: News

The Irish Times | [ View Original Source (opens in new window) ]

by SEÁN FLYNN

PROFILE: PROFESSOR DON BARRY, PRESIDENT, UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK (UL): The University of Limerick has been physically transformed but it still needs to move up the world rankings of leading universities – that’s the next big challenge for its self-effacing president, Don Barry

PROFILE: PROFESSOR DON BARRY, PRESIDENT, UNIVERSITY OF LIMERICK (UL): The University of Limerick has been physically transformed but it still needs to move up the world rankings of leading universities – that’s the next big challenge for its self-effacing president, Don Barry

FOR SUCH A MODEST, self-effacing figure, the UL president, Don Barry has generated a good deal of headlines this year. First, there was controversy about his “lavish” and “extravagant” €1 million home on the campus. Fine Gael leader, Edna Kenny, dived in suggesting the money might have been better spent on student services.

Then, there were those awkward moments at a meeting of the Dáil Public Accounts Committee (PAC) in September when members wanted to know why Barry and two other senior UL figures received a presidential salary during 2006/2007.

It says something for Barry that he has emerged largely unscathed from both controversies. He may not be the life and soul of the party among the seven university presidents, but he is widely respected and much liked.

Says one university figure: “A lot of muck was thrown but none of it has stuck. Don Barry has dusted himself down and moved on. He has been doing an outstanding job . . . in his own quiet way.’’

Quietly, away from the university gossip circuit in Dublin, some spectacular progress is being made at the University of Limerick. For one, the cranes remain on the skyline and the JCBs are still clambering around the campus. Much of this is thanks in large measure to Chuck Feeney, the billionaire philanthropist who has donated over €1 billion to Irish universities, most of it to UL.

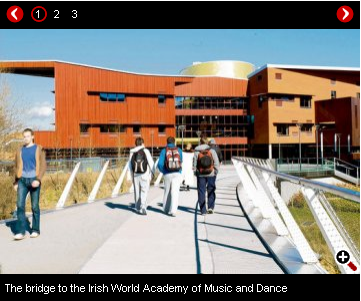

The result? The most impressive range of campus facilities in the State. At its centre is the striking €9 million Living Bridge across the Shannon. It is the longest pedestrian bridge in Ireland, uniting Clare and Limerick in the one campus. Meander across the bridge and your eye will be be drawn towards the new Irish World Academy of Music and Dance, an inspirational environment for music and dance performance.

Then there is the centre for health sciences; the new Kemmy business school; construction of one of the largest all-weather sports pitches in Europe; and new homes for medical post-graduates and their families. And that’s before we mention the best sports facilities and student accommodation of any university in the State.

As president, Don Barry has presided proudly over all of these achievements. But his chief focus remains – not on bricks and mortar – but on the quality of the student experience.

Barry believes strong undergraduate teaching is UL’s core business. He has little truck with high-profile academics in other universities who absent themselves from undergraduate teaching.

He has also invested heavily in the student experience; closely tracking the progress of students during their critical first seven weeks in college and offering crash courses in maths, science and writing skills for undergraduates.

It may explain why UL has the lowest drop-out rate of any Irish university.

Some university figures suggest Barry is a “lucky general’’ who inherited Chuck Feeney’s largesse and secured a graduate medical school for UL, only months into his 10-year term.

But admirers say Barry has made his own luck by working in a collaborative way with senior staff. Says a colleague: “Barry sees himself as part of a team. There is no big ego and no big stick.’’

The son of postal worker from Mallow, Co Cork, Don Barry (53) secured a BSc and MSc in Mathematical Science from UCC. In 1982, he graduated from Yale with a PhD in Statistics.

A former registrar at UL, he was the leading internal candidate when former president Roger Downer stepped down on health grounds in 2006. He was duly appointed president in May 2007.

UL’s success in securing the lion’s share of medical places in March 2007 was an extraordinary coup for a university with no existing medical school.

The decision – made by an international assessment panel – provoked a furious response from the well-established medical schools in Trinity, UCD, UCC and NUI Galway. For Barry, it was the latest example of UL’s “proven capacity to respond to national and regional needs in a bold, innovative way”.

UL has also been quick to seize on the importance of rationalisation across the sector, even before the demand for regional clusters of excellence became de rigeur . In 2006, it established the Shannonside Consortium, bringing together all of the other third level colleges in the region.

Earlier this year, Barry and Jim Browne (his counterpart in Galway) pushed through a new strategic UL/NUIG alliance, building on their combined strength.

The biggest challenge, of course, is to identify the research projects which will spin out companies and deliver jobs.

UL already has one shining star. Earlier this year, Stokes Bio Ltd a UL spin-out company was purchased by California-based Life Technologies for $44 million (€34 million). It was one of the biggest university spin-out acquisitions in the history of the state. In total, six UL campus companies have been set up over the past three years, employing 80 people locally.

But the task of finding employment for UL’s 10,000 undergraduates – ranged across no less than 60 courses – is immense.

Last year, 51 per cent of graduates gained employment, thanks in part to UL’s successful internships or co-op year which allows them get their feet under the table. But with the economy in freefall, things may get worse before they get better for graduates in every university in the State.

For Barry, those twin controversies about his lavish residence and his spat with the PAC were a diversion from the task in hand of consolidating UL’s recent progress.

In characteristic fashion, Barry has chosen to make no public comment – even though the case for the defence is a decent one.

The “lavish’’ residence, demonised in some circles, was actually funded not by the taxpayer but by Chuck Feeney. His vision was of a spacious residence where the president could nurture contacts and spread the good news about UL over cocktails.

On his nomination, Barry explained how the five bedroom, three-storey house was a little too big for his needs. But that cut no ice; it was a condition of the job that the new president would live in the new residence.

The circumstances in which three people were being paid a presidential salary at the same time at UL can also be defended. Former president, Roger Downer actually received the payment from the UL Foundation, not the taxpayer, so that he could continue to work with Feeney and other major donors to the college.

The other beneficiary, Prof John O’Connor, a UL veteran of some 30 years, was co-ordinating the largest capital programme in any Irish university. Did it make sense to take him off the payroll?

Barry told the Public Accounts Committee that the university found itself dealing with “unique, exceptional and very challenging circumstances”.

Around the university sector opinion remains divided about the UL pay issue. Some cast it as a misjudgment at a time of increasing austerity; other see it as an inspired decision in the long-term interests of the university.

For Barry, the whole sorry business has been consigned to history. There are more pressing issues, not least those troublesome world rankings. Despite the physical transformation, UL has the lowest world ranking – 451st – among the seven universities in the State. Barry is looking to his research teams to boost their citations and help propel the university up the rankings. Additional research-active staff for the post-graduate medical school will help. But UL knows it must do better to attract more international and indeed national students. As it is, UL’s student base is largely drawn from the immediate hinterland of Limerick, Tipperary, Clare, north Cork and Kerry.

Despite the quality of its facilities and its strong academic record, the university still struggles to draw students from Dublin and other points north. The negative publicity about gang wars which clings to Limerick does not help. At the height of the conflict five year ago, former president, Roger Downer took to the airwaves to calm fears among prospective students and their parents.

Across the campus, there is a sense among staff and students that it is those who opt to stay away from UL who are losing out. Indeed, one of the defining characteristic of UL is the infectious enthusiasm of staff and students for the place.

There is a messianic zeal to tell you about this development or that. They want you to shed those negative, ill-informed prejudices about Limerick and its environs. And, bursting with pride, they want to tell you about the wonders of their university.

FIVE STARS What makes Limerick different?

1 UL has the most attractive campus in Ireland, thanks to the generosity of Irish American billionaire, Chuck Feeney. Recent additions include Irelands longest pedestrian bridge across the Shannon and the Irish World Academy of Music and Dance.

2 The university has the best sports facilities of any college in the State, including an Olympic-size swimming pool. Construction of one of Europe’s largest all-weather pitch for soccer, rugby, hurling and Gaelic football has begun.

3 The college has the lowest drop-out rate of any university. New students are monitored closely during the first seven weeks.

4 UL offers work placements to 1,500 employers across the globe, one of the biggest programmes of its kind. Typically, aeronatutical engineering students travel to Airbus in France. Those taking Equine Studies go to Kentucky.

5 All first-year undergraduate students are guaranteed accommodation in one of five on-campus student villages.

The University of Limerick is an Atlantic grantee.